One major bias that circulates is that the cause of your pain or injury is usually a tight muscle. But that's an over-simplified look at the problem. Why does the muscle appear tight? From what evidence I've gathered over years, it's a nervous system thing. In other words, there is indeed a reason that a muscle is tight, but to say that is the problem is like saying to a blind person their problem is they can't see. Well...yeah, you've just used words to get nowhere. When I overhear an athlete or even a medical professional just write something off as a tight muscle, I fear the problem of joint centration is not going to be addressed appropriately.

Let me give you an idea as to why this may be a bigger mystery than you think and why it's important for a practitioner and patient to work together to figure this issue out...

A tight muscle gives incorrect input to the central nervous system (CNS).

Likewise, the CNS can provide an input for a muscle to tighten in response to something else (compensation).

Chronic posture or habits can affect muscle length, which again changes input.

Is it the chicken or the egg?

Joint Centration is a dynamic neuromuscular strategy that leads to optimal joint position allowing for the most mechanical advantage. Common reasons for poor joint centration are muscle imbalances (which have a variety of causes), structural injury (acute or chronic), and chronic behaviors (such as bad posture). Furthermore, centration of one joint affects nearby joints, meaning for example that if you do not centrate correctly within your spine (poor posture), you will change your scapular positioning and thus negatively affect the joint centration of your glenohumeral joint (shoulder).

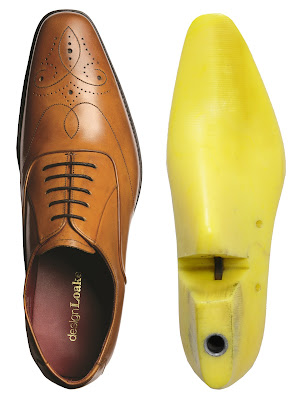

This graphic demonstrates briefly the idea of joint centration. Keep in mind that this is a dynamic process, even with activities that are considered "static" such as our posture. To maintain an upright posture, our postural muscles must maintain a low level of firing. The muscles themselves must not only be strong and endure a full day of activity, but they must be timed properly to allow for consistent joint centration to occur.

When our joints are "seated properly" both statically and dynamically, we allow for maximal use of the surface area, we create the best mechanical advantage for our muscles, and we prevent our passive structures from getting overloaded (examples: the labrums of the hips/shoulders and the menisci of the knees). This process involves a lot more than just the muscles, it involves the command center (CNS: your brain and spinal cord). So while we would like to point the finger at a tight muscle, to actually recover from a joint centration problem it is often more helpful to consider muscles that may be too weak (leading to compensation), the function of other joints (leading to compensation), and the actual movement patterns the person uses to accomplish a task (leading to compensation).

Muscular synergy and joint centration are critical aspects to normal function and must be considered in any rehabilitation program. If performing exercises without proper joint centration, you end up strengthening a muscle in a non-ideal position and pattern, further ingraining compensation into your central nervous system (CNS). It may indeed reduce pain initially, but it can decrease your joint stability over time which ultimately leads to pain and functional problems down the road.

Some important takeaways regarding joint centration...

#1 - While there is nothing wrong with "treating" muscles that are very tight, normal joint mechanics (if able to achieve), are the ultimate goal. This is likely to take weeks and months to properly achieve, usually a quick fix or one treatment does not address the complexities of joint centration or re-training muscle synergy.

#2 - Your chronic habits outside of your formal rehabilitation are critical. Knowing that joint centration in one area affects joint centration in another area, we have to consider our postures and where we hold tension (dealing with our stress in a positive way as opposed to holding it in our bodies). Complete body posture must be considered.

#3 - Don't get overly fixated on joint damage as the source of your pain. This may be the case, but just as likely you have a joint centration problem that lead to degeneration or tearing of a passive structure. This means that your "injury" is the secondary issue, the result of poor joint centration. Focus your efforts on "repairing" the torn structure and you've just endured a very expensive surgery for no reason. If you don't fix the poor joint centration, you maintain inflammation and pain. If you simply try to compensate around the joint centration problem to avoid pain, you create a joint centration problem elsewhere and eventually you'll feel pain there too.

I spend a great deal of time and effort to better understand how to create muscle synergy and good joint centration in my patients. It is an ongoing learning process and one that I will spend my career improving upon...if it were just a tight muscle problem, I could totally stop learning now!